Jean Grémillon

- Knappen

- Joined: Wed Jul 12, 2006 2:14 am

- Location: Oslo/Paris

Re: Jean Grémillon

Or simply mail directly herrschreck@frenchgrammarassistance.fr

- Knappen

- Joined: Wed Jul 12, 2006 2:14 am

- Location: Oslo/Paris

Re: Jean Grémillon

Unexpected Grém paraphernalia has suddenly surfaced right here on the Internet. This has been brought to my attention by our old friend Kinsayder who is still very much alive and collecting movies.

Most of us think of Grémillon as the perfect example of a “cineaste mauditâ€: He burned out having spent most of his creative force on projects that were abandoned or butchered to such a degree that he had his name removed from the final product.

The worst period certainly seem to have been the years following WW2, although he had had a big hit with Le Ciel est à vous in 1944 and received much critical acclaim for the documentary Six juin à l’aube about the bombing of Normandy by the allies. This film, of which I have only seen a couple of scenes, marked a new direction in Grémillon’s career: He now wanted to make films about events that had marked history and he wasn’t going to hide his leftist sympathies when choosing his subjects.

The pet project from the start was a three-part film on the Commune of 1871, for which he did a considerable amount of work on research. When the Commune project was stopped during the work on the scenario, Grémillon and Charles Spaak started right away on a new three-part idea, called Le Massacre des Innocents. It was to be an historical fresco about Spain of 1936, Paris/Munich of 1938 and France of 1944-45. The duo didn’t get very far with this project either. Another film Grémillon wanted to make was to be about a group of Italian actors that arrive in Paris at the night of the St. Bartholomew's Day massacre, called Comedia dell’arte.

It seems that our man hadn’t really given up hope in getting these projects alive, but anyway they were all put aside when he was proposed a big budget project by the Ministry of National Education by the end of 1947. This was to be Le Printemps de la liberté, a grand film celebrating the century of the 1848 revolution. To make a long story short, Grémillon spent an enormous lot of work on preparations, got everything in place and presented his work to a group from the Ministry who was quite positive. Some days later he read in the newspaper that a certain project on the 1848 revolution was to be replaced by something celebrating the death of Chateaubriand the same year.

BUT: to save what could be saved Grémillon made a radio version of his screenplay featuring the actors that he had cast for his film. This version of Le Printemps de la liberté, which was originally broadcast in the summer of 1848, is now available for download here. The price is 6 €, which is a tad stiff considering the poor work INA has done transferring this mostly voice-only recording. But it is a very welcome offer for anyone interested in Grémillon, as he directed the version himself and also has the role of he narrator. The names of the people involved will be familiar to those of you who know his films from the 40s and 50s.

Reading a bit about the events in February and June 1848 will probably pay off for most people. It can also be added that Grémillon published the screenplay the same year and that reading this along with the audio version is very rewarding. I have made a pdf version of the book and am willing to send it to those of you that might be interested. The only condition is that you have prepared enough room and your email account (32 Mb) and some software that can unpack and recompose the 5-part archive file I have made. The text is mostly identical to the radio version with some changes to make things more explicit. It also has plenty of information that doesn’t get through on the audio.

Most of us think of Grémillon as the perfect example of a “cineaste mauditâ€: He burned out having spent most of his creative force on projects that were abandoned or butchered to such a degree that he had his name removed from the final product.

The worst period certainly seem to have been the years following WW2, although he had had a big hit with Le Ciel est à vous in 1944 and received much critical acclaim for the documentary Six juin à l’aube about the bombing of Normandy by the allies. This film, of which I have only seen a couple of scenes, marked a new direction in Grémillon’s career: He now wanted to make films about events that had marked history and he wasn’t going to hide his leftist sympathies when choosing his subjects.

The pet project from the start was a three-part film on the Commune of 1871, for which he did a considerable amount of work on research. When the Commune project was stopped during the work on the scenario, Grémillon and Charles Spaak started right away on a new three-part idea, called Le Massacre des Innocents. It was to be an historical fresco about Spain of 1936, Paris/Munich of 1938 and France of 1944-45. The duo didn’t get very far with this project either. Another film Grémillon wanted to make was to be about a group of Italian actors that arrive in Paris at the night of the St. Bartholomew's Day massacre, called Comedia dell’arte.

It seems that our man hadn’t really given up hope in getting these projects alive, but anyway they were all put aside when he was proposed a big budget project by the Ministry of National Education by the end of 1947. This was to be Le Printemps de la liberté, a grand film celebrating the century of the 1848 revolution. To make a long story short, Grémillon spent an enormous lot of work on preparations, got everything in place and presented his work to a group from the Ministry who was quite positive. Some days later he read in the newspaper that a certain project on the 1848 revolution was to be replaced by something celebrating the death of Chateaubriand the same year.

BUT: to save what could be saved Grémillon made a radio version of his screenplay featuring the actors that he had cast for his film. This version of Le Printemps de la liberté, which was originally broadcast in the summer of 1848, is now available for download here. The price is 6 €, which is a tad stiff considering the poor work INA has done transferring this mostly voice-only recording. But it is a very welcome offer for anyone interested in Grémillon, as he directed the version himself and also has the role of he narrator. The names of the people involved will be familiar to those of you who know his films from the 40s and 50s.

Reading a bit about the events in February and June 1848 will probably pay off for most people. It can also be added that Grémillon published the screenplay the same year and that reading this along with the audio version is very rewarding. I have made a pdf version of the book and am willing to send it to those of you that might be interested. The only condition is that you have prepared enough room and your email account (32 Mb) and some software that can unpack and recompose the 5-part archive file I have made. The text is mostly identical to the radio version with some changes to make things more explicit. It also has plenty of information that doesn’t get through on the audio.

- whaleallright

- Joined: Sun Sep 25, 2005 12:56 am

Re: Jean Grémillon

Does anyone happen to have a copy (in however cruddy condition) of Gardiens de phare? I'm working on a piece on the continuities and ruptures in Grémillon's filmmaking from the late-silent to the early-sound period, and this is the missing link.

- HerrSchreck

- Joined: Sun Sep 04, 2005 11:46 am

Re: Jean Grémillon

The clips I have of G. du phare in the L'Opera Intime doc look fabbo (and the telecine is decades-old analog)

Of course we can instantly recognize Genica Athanasiou, Zita the gypsy from Maldone.

Of course we can instantly recognize Genica Athanasiou, Zita the gypsy from Maldone.

- whaleallright

- Joined: Sun Sep 25, 2005 12:56 am

Re: Jean Grémillon

Yes, I'm using the Sellier, the issue of 1895 devoted to Grémillon, and stray essays here and there. POSITIF seems to have a fondness for Grémillon and has published a few articles about him over the past two decades.

Surely there's a full telecine of GARDIENS DE PHARE somewhere out there. I take it the French print is a later (postwar?) positive made from some earlier print. To my understanding, it's acetate film that undergoes vinegar rot.

Surely there's a full telecine of GARDIENS DE PHARE somewhere out there. I take it the French print is a later (postwar?) positive made from some earlier print. To my understanding, it's acetate film that undergoes vinegar rot.

-

ptmd

- Joined: Wed Nov 03, 2004 1:12 pm

Re: Jean Grémillon

Just to chime in here and avoid having slight misinformation spread, the French print isn't necessarily suffering from vinegar rot (it didn't have the usual smell), but it is slightly warped. It's a very old, 35mm safety print, and I don't know the status of nitrate sources. I viewed it on a Steenbeck and am not aware of any currently accessible telecine transfer (which isn't to say that it doesn't exist somewhere; Schreck's images suggests that it might).

In any case, the film is a masterpiece and I imagine a full restoration could be mounted if there was sufficient interest and, most importantly, money (a very tricky thing these days, especially for a director without the name recognition of Renoir or Carne or Duvivier). Jonah, if you want any more specific information on any of this, feel free to PM me.

In any case, the film is a masterpiece and I imagine a full restoration could be mounted if there was sufficient interest and, most importantly, money (a very tricky thing these days, especially for a director without the name recognition of Renoir or Carne or Duvivier). Jonah, if you want any more specific information on any of this, feel free to PM me.

- Zazou dans le Metro

- Joined: Wed Jan 02, 2008 10:01 am

- Location: In the middle of an Elyssian Field

Re: Jean Grémillon

Jonah,

You don't mention having the Henri Agel monograph which David Hare has listed at the head of this thread. It doesn't go into great detail about Gardiens de Phare but it has a pretty good bibliography and examples of Grémillon's own writings. There happens to be one on e-bayfor a cheap price at present (It's not mine by the way)

You don't mention having the Henri Agel monograph which David Hare has listed at the head of this thread. It doesn't go into great detail about Gardiens de Phare but it has a pretty good bibliography and examples of Grémillon's own writings. There happens to be one on e-bayfor a cheap price at present (It's not mine by the way)

- zedz

- Joined: Sun Nov 07, 2004 7:24 pm

Re: Jean Grémillon

Just checked into this old thread and felt I had to register my dismay that, five years after this discussion was initiated, there are still no English-subbed releases of any of Jean Gremillon's films, as far as I know, even though a tidy handful of French transfers have been out for some time begging for adoption and he was long ago hinted at as being potential Eclipse fodder (with Remorques at least being a confirmed Criterion acquisition, n'est-ce pas?) The wait continues. . .

- tarpilot

- Joined: Thu Jan 20, 2011 10:48 am

Re: Jean Grémillon

kjljkl

Last edited by tarpilot on Wed Mar 25, 2015 1:31 pm, edited 1 time in total.

- tavernier

- Joined: Sat Apr 02, 2005 7:18 pm

- NABOB OF NOWHERE

- Joined: Thu Sep 01, 2005 12:30 pm

- Location: Brandywine River

Re: Jean Grémillon

Well re Gardiens des Phares especially but also hosting showings of some early docos , Maldone and Lise there's this little festival coming up in Lausanne.david hare wrote:Jonah, this is holy grail territory.

There are only two prints in existence, one at the Bois d'Arcy Archives Francaises, and the other one in Vienna.

Richard Suchenski was advised the Fr. print is beginning to undergo vinegar rot, but both he and knappster have seen it and considered it perfectly viewable.

Please let the board know if you do ever track down a source. There is nothing out there in those back channels, alleys and passages!

EDIT: I neglected to mention - are you useing Genevieve Sellier's book as a resource? She has an excellent chapter on Gardiens - well, the whole book is very fine, I only have an argument with her use of colonialism/racism to focus the prism on Dainah. it's far more abstract and poetic than simply a tract.

Any swiss residents or visitors out there can testify to the print source/quality?

- whaleallright

- Joined: Sun Sep 25, 2005 12:56 am

Re: Jean Grémillon

n/a

Last edited by whaleallright on Thu Oct 22, 2020 7:06 am, edited 1 time in total.

- Knappen

- Joined: Wed Jul 12, 2006 2:14 am

- Location: Oslo/Paris

Re: Jean Grémillon

An old friend of ours pointed my attention to this René Chateau surprise:

Two Grémillons are also coming out on Gaumont à la demande: Daïnah and L'Amour d'une femme.

Two Grémillons are also coming out on Gaumont à la demande: Daïnah and L'Amour d'une femme.

- HerrSchreck

- Joined: Sun Sep 04, 2005 11:46 am

Re: Jean Grémillon

Hmmmmm... wonder who that old friend could have been...

- pianola

- Joined: Sat Jan 21, 2012 9:02 am

- Location: London, England

- Contact:

Re: Jean Grémillon

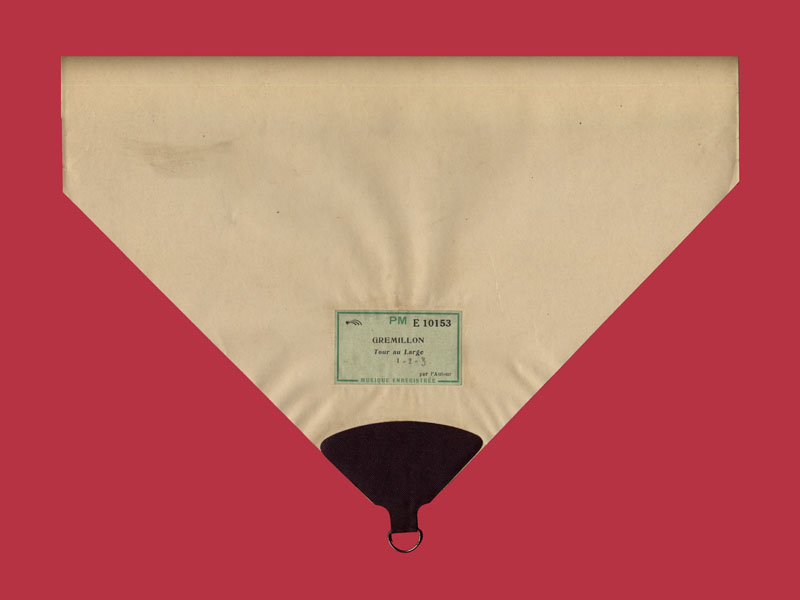

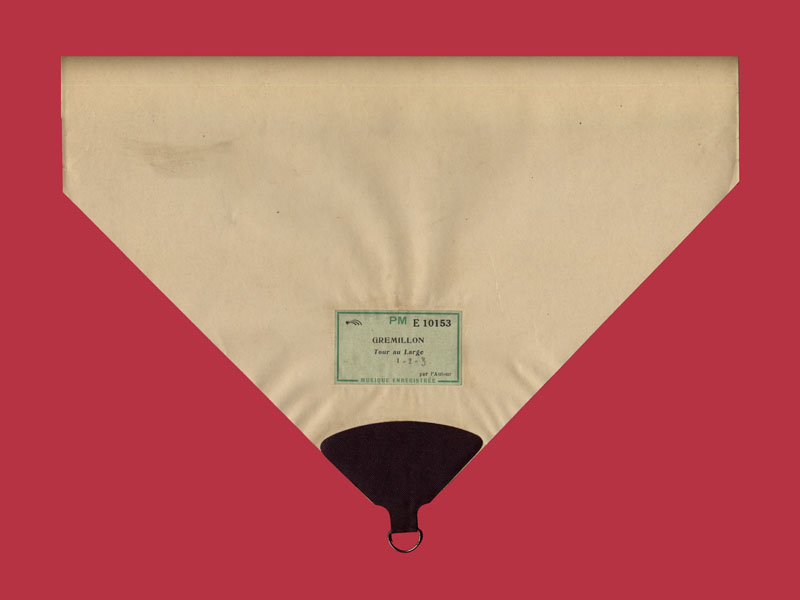

I am a very new member, as of ten minutes ago. I am a specialist in player pianos, and I write the website The Pianola Institute. Two weeks ago I purchased some piano rolls in France (Burgundy), and they included what I believe to be the complete music for "Tour au Large" by Jean Grémillon. Any rolls of this composition are almost non-existent, but in the catalogue they come in three sections, so that the rolls should not be too large for normal player pianos at home. The roll from Burgundy is very long indeed, and although the printed box label mentions part 1, someone has written in ink on the label on the roll itself, adding "-2-3" after the "1". Other rolls in the small collection which I bought suggest someone with a connection to the firm which manufactured rolls for Pleyel, on whose Pleyela roll label "Tour au Large" was issued. The roll was perforated complete, and it is not simply three rolls joined together with sticky tape, so I take it to be a copy of the roll perforated for cinema use.

I am no film expert at all, but I have read on the web that "Tour au Large" is lost. Does that mean that it will never surface, or are there archives where it might be lying uncatalogued? Any information very gratefully received. It would obviously be wonderful to join the music up with the film, and, given how discordant much of it is, it would benefit from what I assume are the pounding waves of a stormy sea. There are also more melodic sections, suggesting whistling seamen offloading tuna at the port, but it might be dangerous to imagine these things in too much detail! I have found one still from the film in a magazine called Cinéa, the issue for April 1st, 1927, which is available on the Bibliothèque Nationale online site, Gallica, which looks pretty grey and squally, like the music!

I live in London, England, and at some point I can record the music, if it is of interest.

Rex Lawson

I am no film expert at all, but I have read on the web that "Tour au Large" is lost. Does that mean that it will never surface, or are there archives where it might be lying uncatalogued? Any information very gratefully received. It would obviously be wonderful to join the music up with the film, and, given how discordant much of it is, it would benefit from what I assume are the pounding waves of a stormy sea. There are also more melodic sections, suggesting whistling seamen offloading tuna at the port, but it might be dangerous to imagine these things in too much detail! I have found one still from the film in a magazine called Cinéa, the issue for April 1st, 1927, which is available on the Bibliothèque Nationale online site, Gallica, which looks pretty grey and squally, like the music!

I live in London, England, and at some point I can record the music, if it is of interest.

Rex Lawson

- NABOB OF NOWHERE

- Joined: Thu Sep 01, 2005 12:30 pm

- Location: Brandywine River

Re: Jean Grémillon

Both the film and the score are noted as lost so that could be some find you have. Perhaps an enquiry with the CNC (site in english) would be a worthwhile step but maybe someone like Ann Harding would be a good person to seek advice from initially.

- whaleallright

- Joined: Sun Sep 25, 2005 12:56 am

Re: Jean Grémillon

n/a

Last edited by whaleallright on Thu Oct 22, 2020 7:06 am, edited 1 time in total.

- NABOB OF NOWHERE

- Joined: Thu Sep 01, 2005 12:30 pm

- Location: Brandywine River

Re: Jean Grémillon

It is indeed registered as "sur rouleau Pleyela Jean Gremillon" so it would seem that he is the composer.jonah.77 wrote:

Does the roll note anything other than the title? Is there a credited composer? Grémillon himself was a trained musician and later a collaborator of Pierre Schaeffer and others, so I wonder if he had a hand in putting this soundtrack together. I also wonder how common it was for integral soundtracks to silent films to be distributed to theaters on piano rolls.

As for the footage there were some clips shown, albeit silent, at the Cinematheque Suisse recently

France | 1926 | 3 min. | version: muet |

Réalisateur(s): Jean Grémillon

Essais de tournage pour Tour au large. A cette époque, il n’était pas rare que l’on projetât de telles «sélections» pour leur valeur photogénique.

As Jonah suggests perhaps Sellier is the go to authority. In the edition Sellier curated for 1895 there is an inventory of al Gremillon's papers deposited at the Bibliotheque Nationale and there doesn't seem to be a copy of this so it looks like you have struck Gremillon oil.

- pianola

- Joined: Sat Jan 21, 2012 9:02 am

- Location: London, England

- Contact:

Re: Jean Grémillon

Just a short note to thank you all for your prompt suggestions. As I said, I am a musician, and tomorrow (Sunday) I am providing Prokofiev to play from rolls at London's Royal Festival Hall, as part of a concert presented and played by the London Philharmonic Orchestra. I have no time to reply properly or to act on any suggestions, therefore, and indeed probably not until Tuesday afternoon or evening, since a friend is coming to stay. I can in due course make a recording, but most piano rolls, despite what you will read elsewhere, do not play themselves. There are no inherent dynamics on Pleyela rolls, so one has to create them musically by pedalling, including accents, crescendos and so on. I need to practise, therefore, and I don't want to record such a find until I know it properly. That isn't to dangle it in front of you, but I guess I need a week or three. I have a friend in the Netherlands with rolls 1 and 2 of the published version, which he found in Normandy last year, as part of a hoard of some 1700 Pleyela rolls. The roll certainly gives Grémillon's name as the composer. I'll scan and upload the label as soon as I have time, and I do speak French, in case anyone needs to know that!

- whaleallright

- Joined: Sun Sep 25, 2005 12:56 am

Re: Jean Grémillon

This is beginning to make more than a bit of sense. "Synchronisme cinématique" was a firm founded by Charles Delacommune specifically to explore the possibilities of distributing films with synchronized soundtracks. I wonder if making and distributing a few "moyens métrages" such as Tour au large served as a kind of "test case" for his experiments. There's some info here--actually a chapter from a book by Swiss scholar Laurent Guido, L'Âge du rythme. Cinéma, musicalité et culture du corps dans les théories cinématographiques françaises 1910-1930. The entire book is here.

Here's the most relevant paragraph (in French, and then in my hasty/sloppy translation):

Delacommune collaborated with Dudley Murphy among others in the French avant-garde, which is a milieu Grémillon would have been close to in this era. It also makes sense in light of Grémillon's career-long attempts to fuse his knowledge of and interest in musical composition with his filmmaking efforts.

In other words, totally fascinating. Like everybody else here, I wait for a recording of this piano roll with bated breath.

Here's the most relevant paragraph (in French, and then in my hasty/sloppy translation):

Les expériences de synchronisation sur disque se multiplient dans les salles parisiennes vers la fin des années 1920. En avril 1927, le compo- siteur et cinéaste Jean Grémillon collabore avec Jacques Brillouin et Maurice Jaubert pour un accompagnement musical au Pleyela destiné à la présentation de son film Tour au large au Vieux Colombier. L’affiche de cette manifestation signale la présence de cette «musique automa- tique»96. Dans son compte rendu de l’événement, Paul Gilson (1927) salue la réussite du synchronisme entre film et musique et la «mise en valeur ou ponctuation des images». Cet instrument lui semble appelé à jouer un rôle essentiel, grâce à son exactitude, inégalée par l’orchestre humain, dans l’accompagnement des images. Par contre, le critique du Ménestrel voit le film souffrir d’une «course, souvent gênante, parfois pathétique, entre deux mécaniques», d’un «synchronisme laborieux entre un jeu plastique et un jeu sonore – machines lancées à des vitesses sensi- blement égales, mais que des écarts de quelques secondes ou de quel- ques fractions de seconde pourront détacher l’une de l’autre». La solu- tion serait alors d’élaborer la relation dynamique elle-même à partir de la musique, comme dans le drame wagnérien et les ballets de Stravinsky, et non du cinéma, d’autant que la musique est ici « automatique » : « Jean Grémillon se trouve pris au piège qu’il s’est lui-même tendu: la rigueur rythmique de son film et la précision mouvante de son film ne laissent aucune marge, aucun répit à la musique.» (Schaeffner 1927)

My guess is that Guido would be very interested in your discovery. He's a professor at the University of Lausanne and his email is Laurent.Guido@unil.ch.Attempts at synchronization via disc increased in Parisian cinemas toward the end of the 1920s. In April 1927, the composer and filmmaker Jean Grémillon collaborated with Jacques Brillouin and Maurice Jaubert on a Pleyela player-piano musical accompaniment prepared for a screening of his film Tour au large at the Vieux Colombier cinema. The publicity for this event advertises this "automatic music." In his account of this event, Paul Gilson (1927) praised the successful synchronization between film and music and its "heightening or punctuation of the images." The player piano seemed to have played an essential role, thanks to its precision--unmatched by a human orchestra--in the accompaniment of the filmed images. On the other hand, the critic for the magazine Ménestrel felt that the film suffered from a "race between two machines--often embarrassing, sometimes just sad"--an "awkward synchronization between image and sound — machines running at ostensibly equal speeds, but with differences of seconds or split-seconds that detach one track from the other." The solution is to develop a dynamic relationship within the music itself, as in the Wagnerian drama or the Stravinsky ballet, and not as in the cinema--especially since the music here is "automatic." [I had trouble translating this previous sentence.] "Jean Grémillon finds himself trapped,: the rhythmic rigor and the moving precision of his film leave no room, no respite for the music." [This might best be translated as something like, "...give the music no room to breathe."]

Delacommune collaborated with Dudley Murphy among others in the French avant-garde, which is a milieu Grémillon would have been close to in this era. It also makes sense in light of Grémillon's career-long attempts to fuse his knowledge of and interest in musical composition with his filmmaking efforts.

In other words, totally fascinating. Like everybody else here, I wait for a recording of this piano roll with bated breath.

- pianola

- Joined: Sat Jan 21, 2012 9:02 am

- Location: London, England

- Contact:

Re: Jean Grémillon

Once again, a general thank you to everyone for enthusiasm and suggestions. I shall have time this weekend to email people, since my wife will be away on her travels (she manages a number of orchestral conductors). One of them, Enrique Mazzola, has recently been appointed as the incoming Music Director of the Orchestre National d'Île de France, and we shall be spending a weekend in Paris in a couple of weeks' time, since he has an opera coming up at the Champs-Élysées. It would be a good time for making new friends.

I think I need to explain some of the background to the use of the player piano in France at this time. For a general history of the instrument, look at http://www.pianola.org" onclick="window.open(this.href);return false;, which I write. It's neither perfect nor complete, but it will give you a good grounding, and there are pages on Stravinsky and on Pleyel, if you look for them.

The question of synchronisation with player pianos keeps cropping up. Stravinsky made a number of versions of his ballet, Les Noces, with different combinations of instruments to accompany it. His second version, dating from 1919, had pianola, two Hungarian cymbaloms, two-manual harmonium and percussion to accompany the choir and soloists. It is often erroneously stated that the version failed on account of the difficulties of synchronising the mechanical and the live instruments, but that was simply to save Stravinsky's blushes, as far as I can see. In 1919 there were no good cymbalom players who could read his music. You got either a wonderful cymbalom player, who could rattle off gypsy music to perfection, but who couldn't read printed scores, or a trained musician who could read, but who had no natural flair for playing such an unusual instrument. Pleyel therefore set about designing a keyboard cymbalom, or rather two of them, but they proved difficult to complete, and they were not ready until 1924. Unfortunately, Stravinsky, always keen on keeping his income flowing, had sold a three-year period of exclusivity for Les Noces to Diaghilev, but had been unable to complete the music in view of the lack of modified cymbaloms. Diaghilev threatened legal action, and Stravinsky had to re-arrange the accompaniment for four pianos and percussion. It was the lack of cymbaloms that caused the trouble, but you often find the pianola taking the blame.

Similarly, George Antheil wrote his Ballet Mécanique for Pleyela in the 1920s, indeed with the intention of having sixteen simultaneous Pleyelas. The film by Fernand Leger came later than the music, I believe, though one can play the first roll in a roughly synchronised way. But although Pleyel had a perfectly reasonable means of synchronising multiple roll-operated instruments together in performance, they didn't have pianola players who could follow a conductor adequately, so they tried to get the conductor to follow the pianos, which was a hopeless task. Consequently the Ballet was never performed with sixteen player pianos, at least not in the 1920s. It has been done in more recent times with Yamaha Disklaviers, though my feeling is that Antheil intended the player pianos to be pedalled furiously, rather like the way in which the humans are enslaved in Fritz Lang's "Metropolis," whereas Disklaviers are impersonal and too smooth. There is no sweat!

The development of the player piano occurred in a variety of ways in different countries. America was really the land of its birth, the British were arguably the most serious at playing it musically, followed perhaps by the Spanish, the Germans specialised in pedalling recorded rolls, the Americans preferred automatic reproducing pianos, and the French created a school of musicians who arranged their music specially for an 88-fingered piano. That is partly as a result of Stravinsky's efforts, but also owes a great deal to the initiative of Jacques Larmanjat, head of music rolls for Pleyel, who surrounded himself with young and willing musical helpers, such as Maurice Jaubert, Pierre-Octave Ferroud, Jean Grémillon and others. But although Pleyel and the Pleyela worked up a whole catalogue section for specially transcribed rolls, they don't seem to have had such a tradition of playing the instrument musically as, for example, the branches of the Aeolian Company and its Pianola, which was originally an Aeolian brand name.

I won't go on and on, but my feeling is that there ought to be no great difficulty in playing the roll of "Un tour au large" in exact time with the film. I'm playing the Grieg Piano Concerto in Illinois in three weeks' time, and accompanying a film can't be any more difficult than that. And yet there is criticism from the 1920s, suggesting that the two media didn't quite fit together as well as they should have done. It all suggests a lack of skill in the use of the tempo control.

I think I'll leave it there for tonight, since I'll need to be up early to get my wife to the airport. My concert Pianola fits in front of a normal grand piano, and one might as well record Grémillon's music on a concert grand if possible. That may take a couple of months to organise, though I have friends at various music colleges in London. I'll be in Paris between 11 and 14 February, which is mostly the weekend, staying in the unfashionable part of Montmartre, over the hill, which is where I especially feel at home in that city. I like meeting people over coffee, by the way!

I think I need to explain some of the background to the use of the player piano in France at this time. For a general history of the instrument, look at http://www.pianola.org" onclick="window.open(this.href);return false;, which I write. It's neither perfect nor complete, but it will give you a good grounding, and there are pages on Stravinsky and on Pleyel, if you look for them.

The question of synchronisation with player pianos keeps cropping up. Stravinsky made a number of versions of his ballet, Les Noces, with different combinations of instruments to accompany it. His second version, dating from 1919, had pianola, two Hungarian cymbaloms, two-manual harmonium and percussion to accompany the choir and soloists. It is often erroneously stated that the version failed on account of the difficulties of synchronising the mechanical and the live instruments, but that was simply to save Stravinsky's blushes, as far as I can see. In 1919 there were no good cymbalom players who could read his music. You got either a wonderful cymbalom player, who could rattle off gypsy music to perfection, but who couldn't read printed scores, or a trained musician who could read, but who had no natural flair for playing such an unusual instrument. Pleyel therefore set about designing a keyboard cymbalom, or rather two of them, but they proved difficult to complete, and they were not ready until 1924. Unfortunately, Stravinsky, always keen on keeping his income flowing, had sold a three-year period of exclusivity for Les Noces to Diaghilev, but had been unable to complete the music in view of the lack of modified cymbaloms. Diaghilev threatened legal action, and Stravinsky had to re-arrange the accompaniment for four pianos and percussion. It was the lack of cymbaloms that caused the trouble, but you often find the pianola taking the blame.

Similarly, George Antheil wrote his Ballet Mécanique for Pleyela in the 1920s, indeed with the intention of having sixteen simultaneous Pleyelas. The film by Fernand Leger came later than the music, I believe, though one can play the first roll in a roughly synchronised way. But although Pleyel had a perfectly reasonable means of synchronising multiple roll-operated instruments together in performance, they didn't have pianola players who could follow a conductor adequately, so they tried to get the conductor to follow the pianos, which was a hopeless task. Consequently the Ballet was never performed with sixteen player pianos, at least not in the 1920s. It has been done in more recent times with Yamaha Disklaviers, though my feeling is that Antheil intended the player pianos to be pedalled furiously, rather like the way in which the humans are enslaved in Fritz Lang's "Metropolis," whereas Disklaviers are impersonal and too smooth. There is no sweat!

The development of the player piano occurred in a variety of ways in different countries. America was really the land of its birth, the British were arguably the most serious at playing it musically, followed perhaps by the Spanish, the Germans specialised in pedalling recorded rolls, the Americans preferred automatic reproducing pianos, and the French created a school of musicians who arranged their music specially for an 88-fingered piano. That is partly as a result of Stravinsky's efforts, but also owes a great deal to the initiative of Jacques Larmanjat, head of music rolls for Pleyel, who surrounded himself with young and willing musical helpers, such as Maurice Jaubert, Pierre-Octave Ferroud, Jean Grémillon and others. But although Pleyel and the Pleyela worked up a whole catalogue section for specially transcribed rolls, they don't seem to have had such a tradition of playing the instrument musically as, for example, the branches of the Aeolian Company and its Pianola, which was originally an Aeolian brand name.

I won't go on and on, but my feeling is that there ought to be no great difficulty in playing the roll of "Un tour au large" in exact time with the film. I'm playing the Grieg Piano Concerto in Illinois in three weeks' time, and accompanying a film can't be any more difficult than that. And yet there is criticism from the 1920s, suggesting that the two media didn't quite fit together as well as they should have done. It all suggests a lack of skill in the use of the tempo control.

I think I'll leave it there for tonight, since I'll need to be up early to get my wife to the airport. My concert Pianola fits in front of a normal grand piano, and one might as well record Grémillon's music on a concert grand if possible. That may take a couple of months to organise, though I have friends at various music colleges in London. I'll be in Paris between 11 and 14 February, which is mostly the weekend, staying in the unfashionable part of Montmartre, over the hill, which is where I especially feel at home in that city. I like meeting people over coffee, by the way!

- pianola

- Joined: Sat Jan 21, 2012 9:02 am

- Location: London, England

- Contact:

Re: Jean Grémillon

I have been reading "l'Age du rythme" by Laurent Guido, and my thanks to Jonah.77 for his suggestion. I've come across one particularly interesting snippet of information, in footnote 98 on page 482. It mentions a certain Monsieur Castillo in connection with Ciné-Latin, where he was apparently in charge of musical matters in 1928. The 55 rolls I found in Burgundy all belonged to F. Castillo, and the coincidence is at first glance too great for it not to have been the same man. The choice of repertoire on the rolls is so recherché that my first thought was that they were only part of a once larger collection, but now I'm not so sure. As well as the Grémillon, they also include music by Jacques Brillouin, Pierre-Octave Ferroud, Marcel Delannoy, Florent Schmitt and Artur Honegger, and they suggest to me someone who was a member of that social circle. There is a three-page article on Maurice Jaubert on the web, based on a biography by François Porcile, and it notes that in 1923 the young Jaubert very quickly made friends with the musicians Jacques Brillouin, Pierre-Octave Ferroud and Marcel Delannoy, with the help of Artur Honegger. Both Ferroud and Jaubert worked for Pleyel and the Pleyela, and as noted above by Jonah.77, Jaubert and Brillouin collaborated with Grémillon on the rolls of "Tour au Large."

Curiously, when I started looking for F. Castillo on the web a couple of weeks ago, I found that an oil painting by him had failed to sell at an auction house near London in mid-December, but it has not been re-listed, and the auctioneers either cannot or will not provide any more information. I'm certain that it was the same F. Castillo, because all his roll boxes are signed by him, and the signature is very characteristic. There was another painter called F. Castillo, a Mexican, just to make life complicated!

One of the rolls is of a piece of light piano music entitled "Syncopétude" by the American pianist and roll arranger, Adam Carroll, which was issued by Pleyel around 1927, played by Maurice Dumesnil. It is a factory roll, with no label, and F. Castillo has written the details and date of the recording, 25 June 1925, in blue pencil, and signed his name on the roll itself. One wonders whether he was perhaps there, since Pleyel never went as far as noting the dates of recording. All in all, it suggests someone in the same social milieu as Grémillon and his friends.

I said I would scan the roll leader and label for "Tour au Large", so here they are:

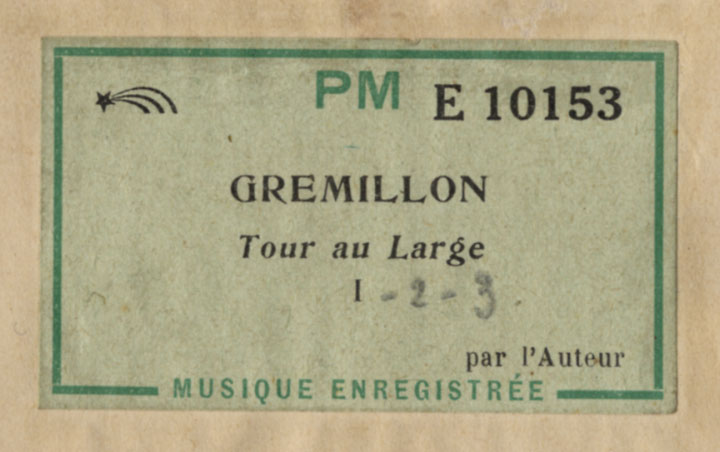

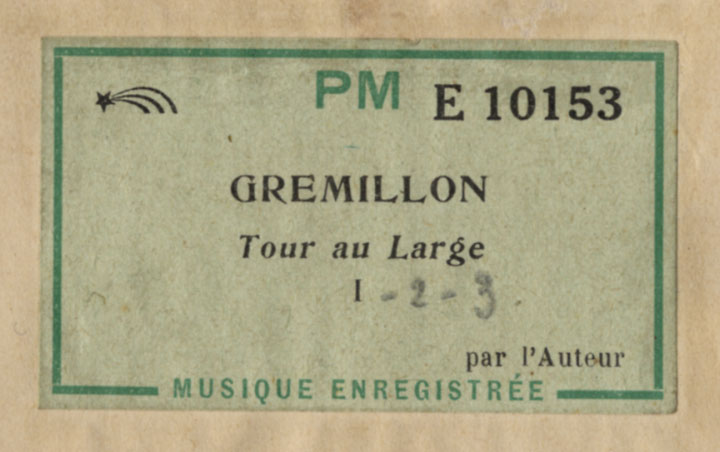

The details of the label will need a little explanation. By the late 1920s Pleyel was in some financial difficulties, caused in part by the disastrous fire at the new Salle Pleyel, at 252 rue du Faubourg St Honoré, and it seems to have divested itself of its music roll activities. Perhaps there was what the English call a "management buy-out", because the rolls continued to be made by the same organisation, which thereafter called itself "La Perforation Musicale". This was located at 22 rue Delambre on the Left Bank, next door to the workshops of Jules Carpentier, who had invented a roll-recording device as early as 1881. Probably this is where Pleyela rolls were always made. At any rate, "PM" stands for "Perforation Musicale".

The small icon at the top left of the label is meant to represent a comet, with its fiery trail, and it stands for the Pleyel trademark of "Perforation Comète". This was a style of perforation in which all notes began with a contiguous slot, but those which were long enough continued with chained perforations, like those on stamp margins. This was a style used throughout the player piano industry, because it helped to strengthen the paper, but Pleyel evidently felt like giving it a ritzy name!

E 10153 is obviously the roll number. The commercial release of "Tour au Large" was on three rolls, E 10153, 10154 and 10155. This roll uses the label for the first of the three, but you can see how someone (presumably F. Castillo) has added "-2-3" in pencil. "E" stands for "Enregistrée", but it doesn't necessarily mean that the roll was recorded by a pianist, and it doesn't mean that there were over 10,000 recorded rolls in the Pleyela/PM catalogue. Like many such companies, Pleyel added to its roll numbers on an ad hoc basis, allocating blocks as the necessity arose. It also published "Rouleaux Métronomiques", and the numbers alternate. 9,000 to 9,999 was a block reserved for accompaniment rolls, both vocal and instrumental, but nothing like that number was published. The "Rouleaux Enregistrées" therefore jumped from 8,999 to 10,000, and similar jumps had occurred previously.

"Tour au Large" is not the sort of music that could normally be played by a pianist, and it was obviously transcribed on to roll by an editor, probably Jaubert. The same process had occurred for Stravinsky's rolls, supervised by the head of Pleyel's roll editing department, Jacques Larmanjat, also a composer, who later became Director of the Conservatoire at Rennes. The fact that the Grémillon music appears in a recorded series simply indicates that the composer had given thought to questions of interpretation, as had Stravinsky, so that the roll can be played through without the need for any heavy manipulation of the tempo control.

I have found a good description of "Tour au Large" in a review for a couple of Dutch language newspapers, which I'll quote here, in a translation in which Google and I agreed to co-operate:

http://www.pianolist.org/gremillon/CA61 ... llouin.mp3" onclick="window.open(this.href);return false;

The recording was made a couple of weeks ago, at a house concert organised by the Friends of the Pianola Institute, on a Steck grand Pianola Piano belonging to a friend of mine in south London. I've added a little reverberation, which I hope suits Brillouin's attempts to mimic a Cavaillé-Coll organ!

By the way, I'll assess the duration of "Tour au Large" and report back. There is no tempo indicated on this particular roll, but I have a friend in Holland with parts 1 and 2 of the published rolls. My guess is somewhere between 15 and 20 minutes, which I assume must be the whole work.

Curiously, when I started looking for F. Castillo on the web a couple of weeks ago, I found that an oil painting by him had failed to sell at an auction house near London in mid-December, but it has not been re-listed, and the auctioneers either cannot or will not provide any more information. I'm certain that it was the same F. Castillo, because all his roll boxes are signed by him, and the signature is very characteristic. There was another painter called F. Castillo, a Mexican, just to make life complicated!

One of the rolls is of a piece of light piano music entitled "Syncopétude" by the American pianist and roll arranger, Adam Carroll, which was issued by Pleyel around 1927, played by Maurice Dumesnil. It is a factory roll, with no label, and F. Castillo has written the details and date of the recording, 25 June 1925, in blue pencil, and signed his name on the roll itself. One wonders whether he was perhaps there, since Pleyel never went as far as noting the dates of recording. All in all, it suggests someone in the same social milieu as Grémillon and his friends.

I said I would scan the roll leader and label for "Tour au Large", so here they are:

The details of the label will need a little explanation. By the late 1920s Pleyel was in some financial difficulties, caused in part by the disastrous fire at the new Salle Pleyel, at 252 rue du Faubourg St Honoré, and it seems to have divested itself of its music roll activities. Perhaps there was what the English call a "management buy-out", because the rolls continued to be made by the same organisation, which thereafter called itself "La Perforation Musicale". This was located at 22 rue Delambre on the Left Bank, next door to the workshops of Jules Carpentier, who had invented a roll-recording device as early as 1881. Probably this is where Pleyela rolls were always made. At any rate, "PM" stands for "Perforation Musicale".

The small icon at the top left of the label is meant to represent a comet, with its fiery trail, and it stands for the Pleyel trademark of "Perforation Comète". This was a style of perforation in which all notes began with a contiguous slot, but those which were long enough continued with chained perforations, like those on stamp margins. This was a style used throughout the player piano industry, because it helped to strengthen the paper, but Pleyel evidently felt like giving it a ritzy name!

E 10153 is obviously the roll number. The commercial release of "Tour au Large" was on three rolls, E 10153, 10154 and 10155. This roll uses the label for the first of the three, but you can see how someone (presumably F. Castillo) has added "-2-3" in pencil. "E" stands for "Enregistrée", but it doesn't necessarily mean that the roll was recorded by a pianist, and it doesn't mean that there were over 10,000 recorded rolls in the Pleyela/PM catalogue. Like many such companies, Pleyel added to its roll numbers on an ad hoc basis, allocating blocks as the necessity arose. It also published "Rouleaux Métronomiques", and the numbers alternate. 9,000 to 9,999 was a block reserved for accompaniment rolls, both vocal and instrumental, but nothing like that number was published. The "Rouleaux Enregistrées" therefore jumped from 8,999 to 10,000, and similar jumps had occurred previously.

"Tour au Large" is not the sort of music that could normally be played by a pianist, and it was obviously transcribed on to roll by an editor, probably Jaubert. The same process had occurred for Stravinsky's rolls, supervised by the head of Pleyel's roll editing department, Jacques Larmanjat, also a composer, who later became Director of the Conservatoire at Rennes. The fact that the Grémillon music appears in a recorded series simply indicates that the composer had given thought to questions of interpretation, as had Stravinsky, so that the roll can be played through without the need for any heavy manipulation of the tempo control.

I have found a good description of "Tour au Large" in a review for a couple of Dutch language newspapers, which I'll quote here, in a translation in which Google and I agreed to co-operate:

Since I am going to wait before I record "Tour au Large", in the main because I need to practise it for a while, I'll give you another musical example for the time being. This is another roll from the Burgundy cache, an arrangement by Jacques Brillouin of the Bach Organ Prelude and Fugue in A minor, BWV 543. I have made several similar roll arrangements over the years, and it was really very moving to discover that someone else had hit on the same ideas of organ harmonics all those years ago. It comes from the "Compositeurs Associés" series of rolls, directed by Brillouin, which included some remarkable stuff, by Honegger, Milhaud, Ibert, Delannoy and so on.Mechanical Film Music

Our correspondent reports from Paris:

Is the question of film music an insoluble puzzle? . . .

Grémillon, an unknown filmmaker, who is also a musician, seems to have discovered the eye of Columbus.

His film, "Tour au Large", which is being shown at the Vieux Colombier, has no plot, no story-line: the starring role is taken by the sea, both calm and stormy, viewed from far and near, flowing slow and fast, interspersed with glimpses of lonely coastlines and fishermen at work.

To translate all this into music, Grémillon perforated rolls for the automatic Pleyela: exploding cataracts of notes, foaming and overflowing into strangely-marbled arabesques; one finds everything "à la minute" in relation to the images, for the Pleyela and the film projector are mechanically connected. The projected scenes, without subtitles, interspersed with restful moments of blackout, correspond exactly with the movements and rests of the music, so that the contrasting effects ("everything includes its opposite") are achieved in the most ingenious way. In the midst of these swirling arabesques, borne on high by the wailing wind (O Sacre du Printemps!), the melodies of a human voice reach out and are heard.

The best thing, since this could all be so close to a banale mimicry in sound - we are far from the sighing and howling of the futuristic orchestra - is that the music is already so carefully styled, that through its suggestions of the secrets of nature it makes for an often almost hallucinatory effect.

The motor car was first a horseless carriage, the film but a silent comedy, and cinema music a succession of nightclub tunes. Now at last the images on film can be accompanied, not "à peu près", but with unerring accuracy by the machine.

Het Centrum, Brussels, 14 April 1927

Nieuwe Tilburgsche Courant, Tilburg, 15 April 1927

http://www.pianolist.org/gremillon/CA61 ... llouin.mp3" onclick="window.open(this.href);return false;

The recording was made a couple of weeks ago, at a house concert organised by the Friends of the Pianola Institute, on a Steck grand Pianola Piano belonging to a friend of mine in south London. I've added a little reverberation, which I hope suits Brillouin's attempts to mimic a Cavaillé-Coll organ!

By the way, I'll assess the duration of "Tour au Large" and report back. There is no tempo indicated on this particular roll, but I have a friend in Holland with parts 1 and 2 of the published rolls. My guess is somewhere between 15 and 20 minutes, which I assume must be the whole work.

- pianola

- Joined: Sat Jan 21, 2012 9:02 am

- Location: London, England

- Contact:

Re: Jean Grémillon

My friend in Holland, Mark Stikkelbroek, who edits the Bulletin of the Nederlandse Pianola Vereniging, has kindly looked at his two Grémillon rolls, and there are no dynamic or tempo markings on those either. The default roll speed in such circumstances is usually 70, which means 7 feet per minute, even in a metric country like France, where Pleyel's equivalent of one inch was 2.5 cm. But from the style of the muic, the speed of repeated notes and so on, I would guess that the roll speed is quite a bit slower. 40 seems nearer the mark, and that would be the same as another long roll that came with this bunch. I would think the roll is somewhere just over 100 feet in length, so speed 40 would give between 25 and 30 minutes of playing time. Would that fit with the length of French shorts in the 1920s?

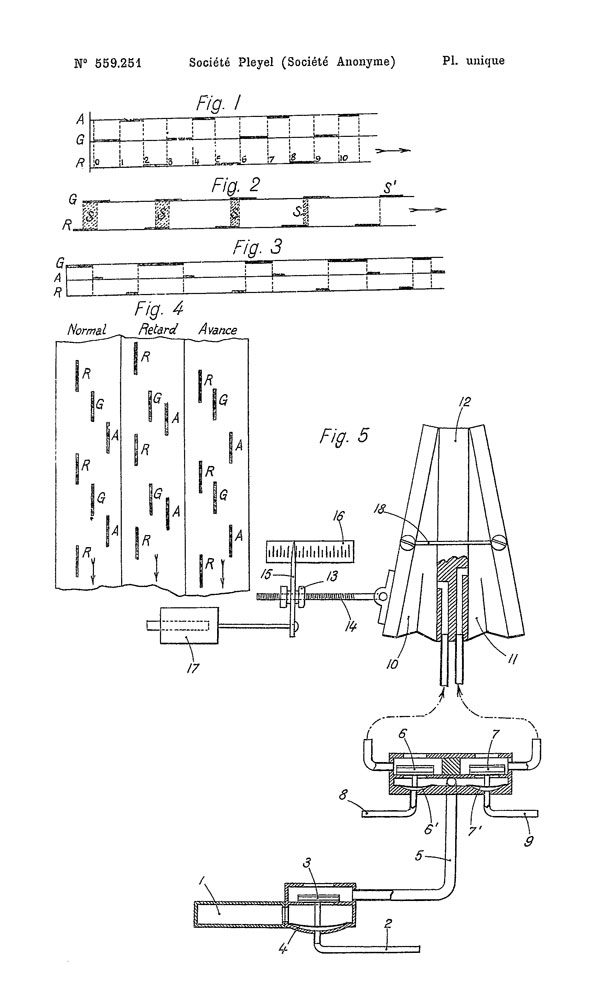

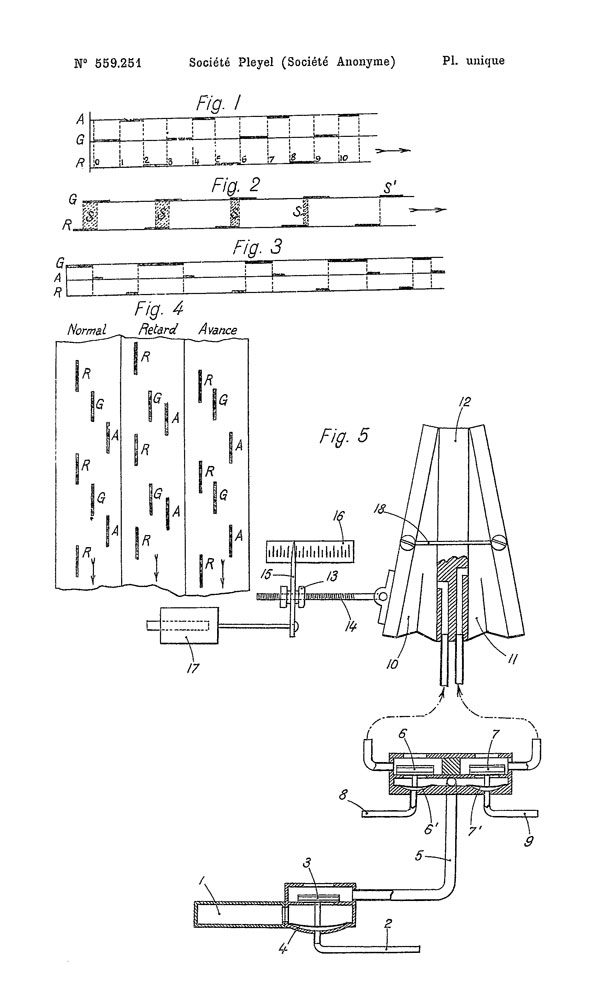

In any case, as I often have to point out to young and enthusiastic musicologists, people a hundred years ago didn't think in the same exact, computer-conscious way that we do nowadays, and speeds can be a very movable feast. The only certain answer would be to rediscover the film and synchronise the two. Anyway, piano rolls are pulled through by a take-up spool, and as the paper builds up, so does the effective diameter of the spool, and as a result the paper speed accelerates. You compensate automatically for that when you are playing the pianola, assuming you have the ears to tell the difference. Pleyel had a synchronisation patent, however, described in French patent no. 559,251. It was originally designed for playing different roll-operated instruments together, but I'm sure it could have been modified to encompass projectors. A regular pulsed perforation at the edge of the roll on the master instrument triggered an electrical pulse that was sent to any slaves that needed to be synchronised. The same pulsed perforations were present on the rolls on the slaves, but in the adjacent perforation tracks on each side were two other series of pulses, one in advance and the other in arrears. If the slave received its sync pulse while the advance pulse was still open, it mean that the slave roll was a little slow, and if the arrears pulse had already appeared, then the slave was running slightly fast. A double pneumatic was operated by valves triggered by these various perforations and adjusted the tempo lever as necessary. It was essentially a very early form of feedback.

Here's a picture of the synchronisation mechanism:

We have a perforating machine here (who doesn't!), and I can imagine I shall be making copies of the Grémillon 'ere long. It would be good to see it distributed in small quantities and thereby becoming a little safer. But that does open up another can of worms, which is that if you want to play the pianola properly, you have to study, just as you do with any other instrument. It's like conducting, since those chaps play no notes by hand either, and everyone starts by thinking that there's nothing to it, which is why so many of the pianola videos on YouTube are so awfully unmusical. Ah, and concert audiences nowadays, in Britain at least, go to watch music more than to listen to it. They like the folk who wave their arms around a lot, because they think fast movement is clever. But I digress!

In any case, as I often have to point out to young and enthusiastic musicologists, people a hundred years ago didn't think in the same exact, computer-conscious way that we do nowadays, and speeds can be a very movable feast. The only certain answer would be to rediscover the film and synchronise the two. Anyway, piano rolls are pulled through by a take-up spool, and as the paper builds up, so does the effective diameter of the spool, and as a result the paper speed accelerates. You compensate automatically for that when you are playing the pianola, assuming you have the ears to tell the difference. Pleyel had a synchronisation patent, however, described in French patent no. 559,251. It was originally designed for playing different roll-operated instruments together, but I'm sure it could have been modified to encompass projectors. A regular pulsed perforation at the edge of the roll on the master instrument triggered an electrical pulse that was sent to any slaves that needed to be synchronised. The same pulsed perforations were present on the rolls on the slaves, but in the adjacent perforation tracks on each side were two other series of pulses, one in advance and the other in arrears. If the slave received its sync pulse while the advance pulse was still open, it mean that the slave roll was a little slow, and if the arrears pulse had already appeared, then the slave was running slightly fast. A double pneumatic was operated by valves triggered by these various perforations and adjusted the tempo lever as necessary. It was essentially a very early form of feedback.

Here's a picture of the synchronisation mechanism:

We have a perforating machine here (who doesn't!), and I can imagine I shall be making copies of the Grémillon 'ere long. It would be good to see it distributed in small quantities and thereby becoming a little safer. But that does open up another can of worms, which is that if you want to play the pianola properly, you have to study, just as you do with any other instrument. It's like conducting, since those chaps play no notes by hand either, and everyone starts by thinking that there's nothing to it, which is why so many of the pianola videos on YouTube are so awfully unmusical. Ah, and concert audiences nowadays, in Britain at least, go to watch music more than to listen to it. They like the folk who wave their arms around a lot, because they think fast movement is clever. But I digress!

- pianola

- Joined: Sat Jan 21, 2012 9:02 am

- Location: London, England

- Contact:

Re: Jean Grémillon

Hello to all. I don't have much time at present, so this is just a brief post. I'm in Paris this weekend, and on Monday afternoon I'm hoping to visit François Porcile. I've emailed the BN, but I guess it will take them quite a while to contemplate making rolls available for consultation. They have had 650 of them since about 1990, but they are not catalogued. I shall aim to record Tour au Large during March or soon after, once I get home from the US. One distinct possibility is that I shall have access to a Steinway concert grand for rehearsal in mid-April, and I could imagine I might get the odd half-hour on my own, which would be a good opportunity. I see no reason not to use a good-sized piano, even though the early cinemas might only have had uprights. Pleyel made many grand player pianos as well, Grémillon was a trained musician, and unlike Conlon Nancarrow, there would have been no reason for him to associate piano rolls specifically with slightly metallic uprights.

It seems to me that the logic of his music derives from the lost film. It is not like a sonata, with recognisable thematic development, but there are huge whooshes of sound, sometimes repeated, sometimes not: lightning-speed chromatic glissandos, for example, which presumably accompany vast, breaking waves at sea. I think I detect ships' bells and engines, and some fishermen's whistles as well, but I'd better not be too imaginative, against the day someone finds the actual film!

It seems to me that the logic of his music derives from the lost film. It is not like a sonata, with recognisable thematic development, but there are huge whooshes of sound, sometimes repeated, sometimes not: lightning-speed chromatic glissandos, for example, which presumably accompany vast, breaking waves at sea. I think I detect ships' bells and engines, and some fishermen's whistles as well, but I'd better not be too imaginative, against the day someone finds the actual film!

- NABOB OF NOWHERE

- Joined: Thu Sep 01, 2005 12:30 pm

- Location: Brandywine River

Re: Jean Grémillon

Gaumont have hinted that 'Pattes Blanches' will be out by the end of the year. G a la Demande,so HoH subs only.